Diego Rivera Mural in Palacio De Bellas Artes Revolution

Diego Rivera, "From the Conquest to 1930," History of Mexico murals, 1929–xxx, fresco, Palacio Nacional, United mexican states Metropolis

How is history told?

Typically, we think of history as a series of events narrated in chronological club. But what does history look like every bit a serial of images? Mexican creative person Diego Rivera responded to this question when he painted The History of Mexico, as a series of murals that span three large walls within a k stairwell of the National Palace in United mexican states City. In Rivera's words, the mural represents "the entire history of United mexican states from the Conquest through the Mexican Revolution . . . down to the ugly nowadays."[1]

In an overwhelming and crowded composition, Rivera represents pivotal scenes from the history of the modern nation-state, including scenes from the Spanish Conquest, the fight for independence from Espana, the Mexican-American state of war, the Mexican Revolution, and an imagined hereafter United mexican states in which a workers' revolution has triumphed. Although this landscape cycle spans hundreds of years of Mexican history, Rivera concentrated on themes that highlight a Marxist estimation of history as driven by class conflict as well every bit the struggle of the Mexican people against strange invaders and the resilience of Indigenous cultures.

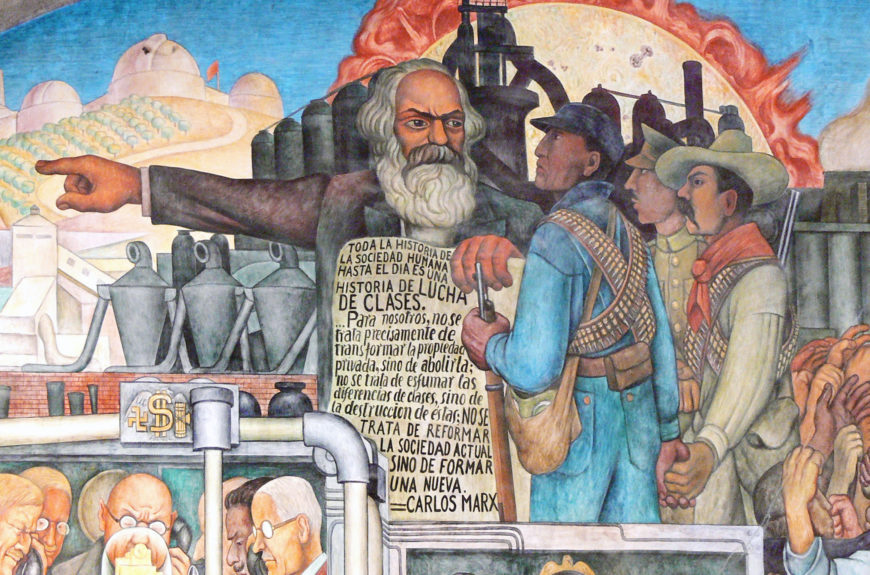

Diego Rivera, "Mexico Today and Tomorrow," detail featuring Karl Marx, History of Mexico murals, 1935, fresco, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City (photograph: Wolfgang Sauber, CC BY-SA 3.0)

A new national identity

In the immediate years post-obit the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920), the newly formed government sought to establish a national identity that eschewed Eurocentrism (an accent on European culture) and instead heralded the Amerindian. The upshot was that Ethnic culture was elevated in the national discourse. After hundreds of years of colonial dominion and the Eurocentric dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, the new Mexican state integrated its national identity with the concept of indigenismo, an ideology that lauded United mexican states'southward past Indigenous history and cultural heritage (rather than acknowledging the ongoing struggles of gimmicky Indigenous people and incorporating them into the new state governance).

José Vasconcelos, the new authorities'due south Minister of Public Pedagogy, conceived of a collaboration between the regime and artists. The outcome were state-sponsored murals such as those at the National Palace in United mexican states City.

Why murals?

Rivera and other artists believed easel painting to be "aristocratic," since for centuries this kind of art had been the purview of the aristocracy. Instead they favored landscape painting since it could present subjects on a big scale to a wide public audience. This thought—of directly addressing the people in public buildings—suited the muralists' Communist politics. In 1922, Rivera (and others) signed the Manifesto of the Syndicate of Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptors, arguing that artists must invest "their greatest efforts in the aim of materializing an art valuable to the people."[two]

Diego Rivera, History of Mexico murals, 1929–30, frescos in the stairwell of the Palacio Nacional, Mexico City

Rivera had to design his composition around the pre-existing congenital surround of the National Palace. Rivera painted in the historical buon fresco technique, in which the artist paints directly upon moisture plaster that has been applied to a wall resulting in the paint being permanently fused to the lime plaster. Such murals were common in pre-conquest Mexico also as in Europe.

In the example of The History of Mexico, this meant creating a three-office allegorical portrayal of Mexico that was informed past the specific history of the site. Today the National Palace is the seat of executive power in Mexico, but it was built atop the ruins of the Aztec emperor Moctezuma 2'southward residence after the Castilian Conquest of the uppercase of Tenochtitlan in 1521. The site then served as the residence of the conquistador Hernán Cortés and later the Viceroy of New Spain until the end of the Wars of Independence in 1821. This site is a potent symbol of the history of conflict between Indigenous Aztecs and Spanish invaders.

North wall: Diego Rivera, "The Aztec World," History of Mexico murals, 1929, fresco, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City (photograph: Gary Todd, CC0)

The North Wall

Quetzalcoatl, particular, Bernardino de Sahagún and collaborators, Florentine Codex, vol. one, 1575–1577 (Medicea Laurenziana Library, Florence, Italian republic)

The Aztec Globe, the title of the mural on the North Wall, features Rivera's first large-scale rendering of Mesoamerica before the Spanish invasion—here focused on the Aztecs (the Mexica). Rivera's representation of the deity Quetzalcoatl ("feathered ophidian"), seated in the center of the composition wearing a headdress of quetzal feathers—draws on imagery from colonial-era sources, in particular, an image of Quetzalcoatl from the Florentine Codex.

Confronting the properties of the Valley of United mexican states (where Tenochtitlan and now Mexico Urban center are located), Rivera renders a Mesoamerican pyramid and various aspects of Aztec life. He represents figures grinding maíz (corn) to make tortillas, playing music, creating paintings, sculpture, and leatherwork, and transporting goods for trade and purple tribute.

Annotated image of the north wall: Diego Rivera, "The Aztec World," History of Mexico murals, 1929, fresco, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City (photo: Gary Todd, CC0)

Despite Rivera's great adoration for pre-Conquest civilizations (he was a peachy collector of pre-Columbian art) he did not uncritically portray the Aztec world as utopian. In addition to rendering scenes of agriculture and cultural production, The Aztec World shows laborers building pyramids, a grouping resisting Aztec control, and scenes of the Aztecs waging the wars that created and maintained their empire. Rivera demonstrates the Marxist position that form disharmonize is the prime driver of history—here, fifty-fifty before the inflow of the Spaniards.

Westward wall: Diego Rivera, "From the Conquest to 1930," History of Mexico murals, 1929–30, fresco, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City (photo: xiroro, CC BY-NC-ND two.0)

The Westward Wall

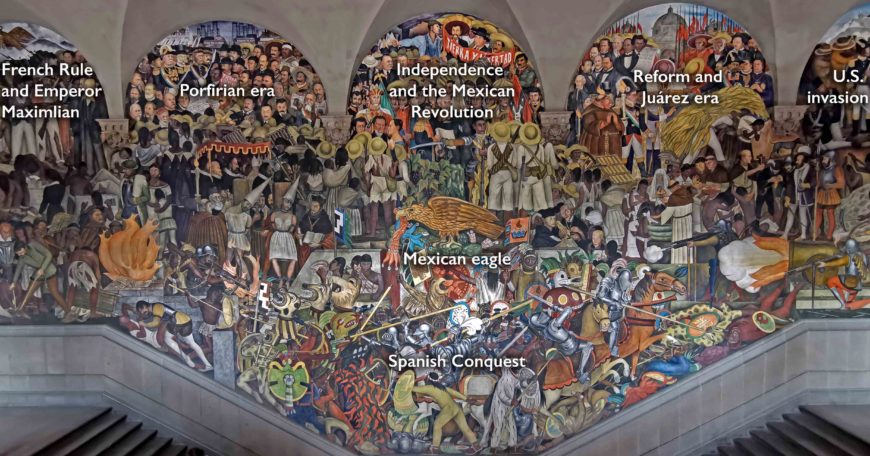

On the West Wall and in the center of the stairway, visitors are confronted with a chaotic composition titled From the Conquest to 1930. The wall is divided at the top past corbels from which leap five arches.

Annotated epitome of the due west wall: Diego Rivera, "From the Conquest to 1930," History of United mexican states murals, 1929–30, fresco, Palacio Nacional, United mexican states City (photograph: drkgk)

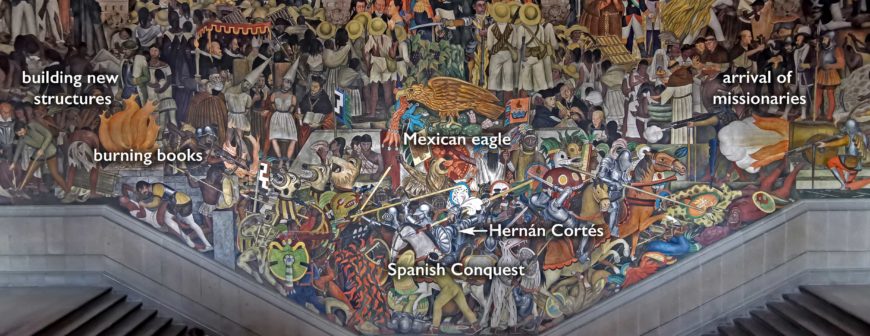

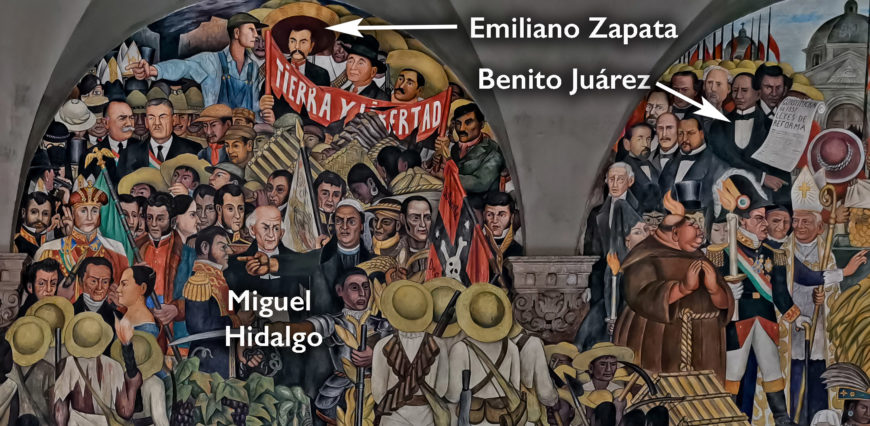

Across the elevation, In the outermost sections, Rivera represents the two nineteenth-century invasions of Mexico—past France and the Us respectively. From left to right, the three key sections depict: the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, figures associated with Independence and the Mexican Revolution, and the Constitution of 1857 (during the presidency of Benito Juárez) and the War of Reform. These historical events are somewhat distinguishable cheers to the arches that separate the scenes.

Annotated lower section of the west wall: Diego Rivera, "From the Conquest to 1930," History of Mexico murals, 1929–30, fresco, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City (photo: drkgk)

In the lower section of the mural however, in that location is no such distinction between, for example, scenes of the Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire, the subsequent destruction of Mesoamerican painted books (at present called codices), the arrival of Christian missionaries, the destruction of pre-Columbian temples, and construction of new colonial structures—emphasizing the interrelated nature of these events.

Eagle on cactus (item), Diego Rivera, "From the Conquest to 1930," History of Mexico murals, 1929–30, fresco, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City (photo: Sarahh Scher, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Mexican flag

An eagle continuing on a nopal cactus at the very center of the wall, mirrors the insignia at the center of the Mexican flag. These historical scenes have been compressed and flattened on the flick surface resulting in a dense visual mosaic of intertwining figures and forms. The lack of deep space in the composition makes it hard to distinguish between unlike scenes, and results in an allover composition without a central focus or a articulate visual pathway. This cacophony of historical figures and flurried activeness overwhelms viewers every bit they walk up the stairs.

Annotated upper section of the due west wall: Diego Rivera, "From the Conquest to 1930," History of Mexico murals, 1929–30, fresco, Palacio Nacional, Mexico Metropolis (photograph: drkgk)

Given the breadth of the wall space, Rivera had to make critical decisions almost which historical figures and narratives to include. Rivera'south formal choices—the flattening of the pictorial space, the nonlinear arrangement, and the monumental calibration of the figures—create a non-hierarchical limerick. These formal choices support Rivera'due south conclusion to represent not but the historically well-known and recognizable figures, such as the independence fighter Miguel Hidalgo, revolutionary Emiliano Zapata (who holds a flag with the words tierra y libertad, or land and liberty), or the first Ethnic president Benito Juárez, only besides anonymous workers, laborers, and soldiers. As Rivera later on noted,

"Each personage in the mural was dialectically continued with his neighbors, in accordance with his part in history. Nothing was solitary; nothing was irrelevant."[3]

The creative person's portrayal of the interconnection of social struggle throughout Mexico's history and the not-hierarchical representation of the historical figures reflects his Marxist perspective.

South wall: Diego Rivera, "Mexico Today and Tomorrow," History of Mexico murals, 1935, fresco, Palacio Nacional, United mexican states City (photograph: Cbl62, CC0)

The South Wall

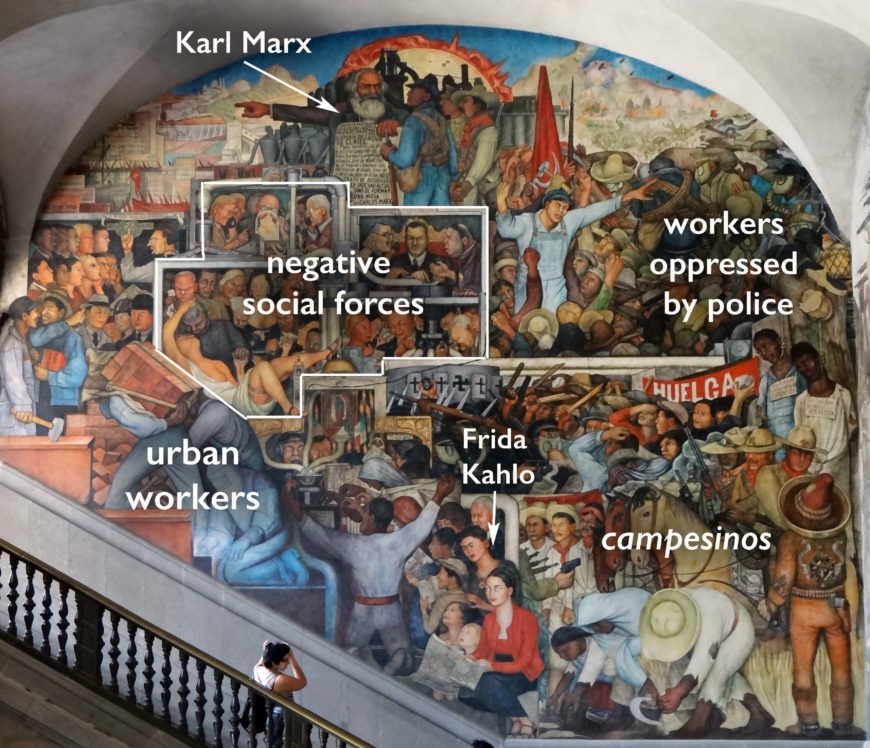

Rivera's politics become more evident on the Southward Wall, titled United mexican states Today and Tomorrow, which was painted years later in 1935. United mexican states Today and Tomorrow depicts gimmicky class conflict between industrial commercialism (using machinery and with a clear sectionalization of labor) and workers around the world.

Annotated image of the south wall: Diego Rivera, "Mexico Today and Tomorrow," History of United mexican states murals, 1935, fresco, Palacio Nacional, United mexican states Metropolis (photo: Cbl62, CC0)

The narrative begins in the lower right and progresses upwards in a boustrophedonic blueprint (here, a reverse Southward-curve), similar to the compositional layout of pre-Conquest Mesoamerican painted manuscripts (such every bit the Codex Nuttall). In the lower department Rivera depicts campesinos (peasant farmers) laboring, urban workers constructing buildings, and his wife Frida Kahlo with a number of schoolhouse children who are being taught as part of an expansion of rural education after the Revolution.

Frida Kahlo wearing a necklace with a ruby star and hammer and sickle pendant (detail), Diego Rivera, "Mexico Today and Tomorrow," History of Mexico murals, 1935, fresco, Palacio Nacional, United mexican states Urban center (photo: Jen Wilton, CC Past-NC 2.0)

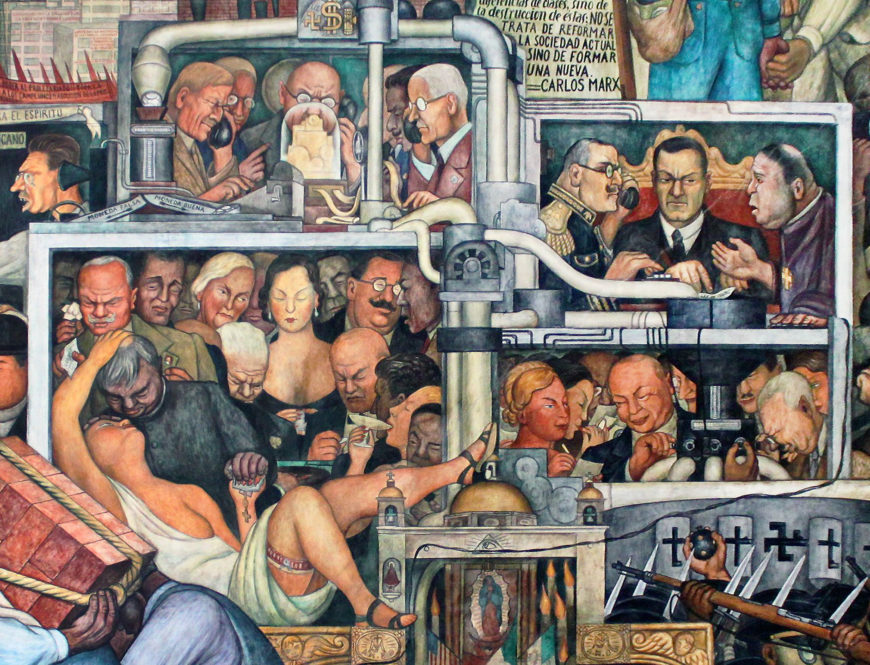

Following the narrative upwards, Rivera represents—using a pictorial structure unique to this wall—negative social forces such equally high-guild figures, decadent and reactionary clergy, and the invasion of foreign capital—here represented by contemporaneous capitalists such as John D. Rockefeller, Jr. who was attempting to secure access to Mexican oil at the time.

Negative social forces—showing capitalist abuse and greed (item), Diego Rivera, "Mexico Today and Tomorrow," History of Mexico murals, 1935, fresco, Palacio Nacional, Mexico Metropolis (photo: Carlos Villarreal, CC BY-NC 2.0)

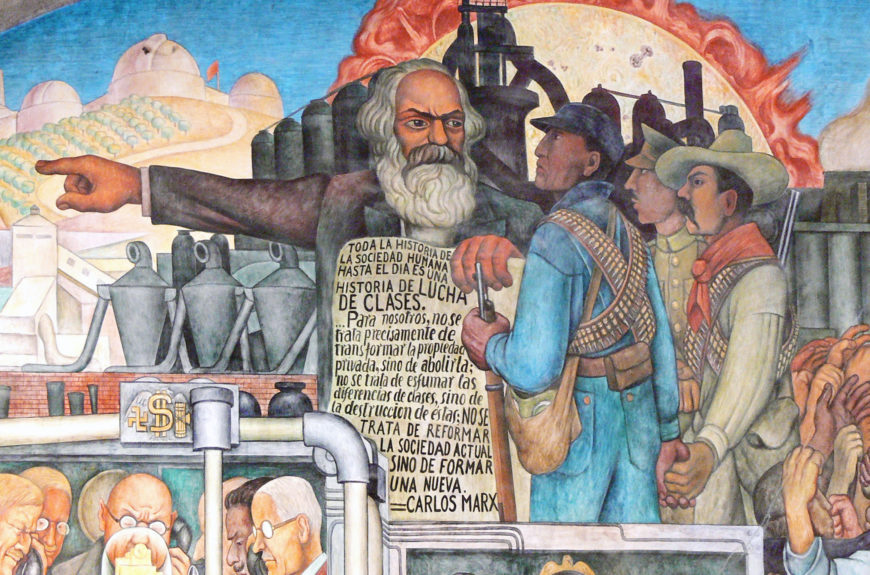

To the right, workers are being oppressed by police wearing gas masks, yet merely above this scene a figure in blue emerges from a mass of uprising workers, their fists raised in the air confronting the backdrop of downtown United mexican states Metropolis. The narrative culminates in a portrait of Karl Marx who is shown pointing wearied workers and campesinos towards a "vision of a future industrialized and socialized land of peace and plenty."[4] Different the not-linear limerick of the West Wall, here Rivera expresses his vision for the future of Mexico, a winding path that leaves oppression and corruption behind.

Diego Rivera, "United mexican states Today and Tomorrow," detail featuring Karl Marx, History of Mexico murals, 1935, fresco, Palacio Nacional, Mexico Urban center (photo: Wolfgang Sauber, CC BY-SA 3.0)

An alternative history

So what type of history has Rivera told us and how did he tell information technology? Is he the sole narrator? The History of United mexican states was painted in a governmental edifice as part of a campaign to promote Mexican national identity, and nevertheless, the mural wheel is non necessarily didactic. Rivera could have created a much simpler representation of Mexican history, i that directed the viewer's experience more than explicitly. Instead, the viewer's response to this visual avalanche of history is to play an active part in the estimation of the narrative. The lack of illusionistic space and the flattening of forms creates a composition that allows the viewer to decide where to look and how to read it. Moreover, the experiential and sensorial human activity of moving up the stairs allows the viewer to perceive the murals from multiple angles and vantage points. In that location is no "right way" to read this landscape because there is no clear beginning or terminate to the story. The viewer is invited to synthesize the narrative to construct their own history of United mexican states.

Notes:

- Diego Rivera, My Art, My Life: An Autobiography (New York: Dover Publications, 1991), pp. 94–95.

- "Manifesto of the Syndicate of Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptors," published in Alejandro Anreus, et.al, Mexican Muralism : A Critical History (Berkeley: Academy of California Press, 2012) pp. 319–321. Signed by Diego Rivera, Davíd Alfaro Siqueiros, Xavier Guerrero, Fermín Revueltas, José Clemente Orozco, Ramón Alva Guadarrama, Germán Cueto, and Carlos Mérida and published in the journal El Machete in June 1924.

- Diego Rivera, My Art, My Life: An Autobiography, pp. 100–101.

- Diego Rivera, My Fine art, My Life: An Autobiography, p. 131.

Additional resource:

Learn more than about Rivera'south murals, including Man Controller of the Universe, Sugar Cane, and the Detroit Industry murals.

Alejandro Anreus, et.al, Mexican Muralism: A Critical History (Berkeley: University of California Printing, 2012).

David Craven, Diego Rivera Every bit Epic Modernist (New York; London: Yard.1000. Hall; Prentice Hall International, 1997).

Diego Rivera, My Art, My Life: An Autobiography (New York: Dover Publications, 1991).

Leonard Folgarait, Mural Painting and Social Revolution in Mexico, 1920-1940 (Cambridge; New York, NY: Cambridge UP, 1998).

Source: https://smarthistory.org/mexico-diego-rivera-murals-national-palace/

0 Response to "Diego Rivera Mural in Palacio De Bellas Artes Revolution"

Postar um comentário